"Oh miracle—thus to be able to give what we ourselves do not possess, sweet miracle of our empty hands!" (Georges Bernanos, Diary of a Country Priest)

Sunday, December 30, 2018

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Sunday, December 23, 2018

Sunday, December 16, 2018

Saturday, December 15, 2018

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Sunday, November 25, 2018

Sunday, November 11, 2018

Follow the Pattern

It will be quiet around here next Sunday, as I'm headed out today for my annual retreat. Pray for me!

Thirty-Second Sunday in Ordinary Time B

Sunday, November 4, 2018

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Sunday, October 21, 2018

Sunday, October 14, 2018

Sunday, October 7, 2018

Making Plans

Twenty-Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time B

Know how to make God laugh? Tell him your plans...

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Sunday, September 2, 2018

By Heart

Twenty-Second Sunday in Ordinary Time B

I come from a long, long line of serious pinochle players. When I was a kid, we’d all pile into the station wagon every Sunday night and head over to my grandparents’ house where Mom and Dad, Mémère and Pépère, would play hand after hand of cards. (In fact, my parents still go over on Sunday nights to play pinochle with my 93-year-old grandmother.)

As a kid, I would try to follow the game—to learn the many rules about bids, suits, runs, trump, tricks, points…but I just couldn’t keep it all straight in my head. (I clearly didn’t inherit the Giroux pinochle gene.) To play pinochle well, you need to know the rules by heart—to the point where you don’t need to consciously think about them anymore—so that you can develop some strategy and finesse. But once you know the rules by heart, then you can really get down to playing your cards—and playing your partner and your opponents as well. One thing I did learn watching so many pinochle games was that, if you play fast and loose with the rules, or if you forget something or make a mistake…watch out! Your error will be called out.

The rules that govern pinochle give the game shape, providing order and structure. The rules are there to protect the game’s integrity. And, although we very rarely think of it that way, the rules are there to preserve the fun. Without all those rules, pinochle would be no fun at all.

Our first reading this Sunday comes from the Book of Deuteronomy. It’s not exactly on the best seller list of the books of the Bible. When the scriptures refer to “the law,” they’re usually referring to Deuteronomy…which makes it sound about as interesting as reading New York State traffic laws or the U.S. tax code. But Deuteronomy is actually a crucial book for the people of Israel and, therefore, also crucial for us. So let us explore two aspects of Deuteronomy that are especially worth our consideration this Sunday.

(1) Since Deuteronomy is a book of laws, what would you expect the most commonly repeated words to be? Probably “thou shalt” or “thou shalt not,” right? But the most common word in Deuteronomy is “heart.”

That’s why God’s law exists: to protect the integrity of your heart. We’ve somehow developed the false notion that rules are made to restrict our freedom; but, especially when it comes to divine law, the opposite is actually true: the rules are there to enhance our freedom. Imagine trying to play cards or Scrabble or golf or baseball when every player makes his or her own rules—anything goes. That wouldn’t be a game; it’d be chaos! Instead of having fun, you’d be incredibly frustrated. God’s law is there to provide necessary order, to give essential structure.

Just like in a game, God’s law only really works when we know it by heart. Now, I don’t just mean memorizing the 10 Commandments (although that’s a very, very good idea). What I mean is more like what we heard this morning from the Letter of St. James: that we are to welcome God’s that is planted in us. It’s not enough to hear and repeat it; we must be doers of God’s word. That’s what Jesus is getting at, too, when he quotes the prophet Isaiah to the Pharisees: “This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me.” When it comes to the law of God, merely going through the motions won’t do. When I obey God, I have to put my heart into it, and allow it to be put in into my heart—planted deep.

God’s law was never meant to be imposed harshly from the outside, left carved into cold tablets of stone; it demands to be inscribed on the fleshy tablets of the human heart. It’s not enough to study and recite the moral law. It’s not enough to accomplish all the required externals—making sure we appear all clean and tidy on the outside. It’s not enough to call out corruption where we see it in others. God’s law is meant to become part of the very fabric of our lives. We must know it by heart, in the deepest sense.

(2) In the Book of Deuteronomy, Moses doesn’t simply relay law after law in an apparently endless list. He puts it into context by retelling much of Israel’s history. When the people need to remember who they are, they look to Deuteronomy. And in that retelling, Moses seems to include this warning: you have not learned from your own past.

Certainly, Moses recalls the many blessings God has given and wonders he has done. But he also recounts what happens whenever Israel takes these blessing for granted, or is unfaithful in observing the covenant, or makes compromises with other nations—whenever this people gets neglectful of God and his law: utter collapse and total ruin. Everything falls apart! In fact, as we can see time and again in the Old Testament, God will use the enemies of Israel—the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Romans—to expose the infidelity, the ugliness, the evil, the wickedness, the filth, the sin of his people. The Lord doesn’t allow this in order to humiliate them, but to provide them with the opportunity to repent, to reform, to be converted. Getting their sin out into the open is the first step toward being healed.

But there’s another pattern that must be noticed running right alongside this one: even when they’ve been most unfaithful to God, God has always remained faithful to them. God is a loving Father who does not, cannot, will not ever, ever change.

At the end of our few verses from Deuteronomy today, Moses tells the people that this law they’ve been given will be evidence of Israel’s greatness among the nations. That’s not simply to say they can stand tall because they’ve got better rules than everyone else (although that’s true); instead, it’s meant to reveal how very close God is to this people. This is not their own doing, not a point of pride. They didn’t chose the Lord; the Lord choose them. Israel’s duty to be faithful to the law is not in order to appease a stern, grumpy God preoccupied with the rules, but is rather to show to the rest of the world what it looks like to stay close to God so that all peoples will be attracted to it and desire it for themselves.

Living by God’s law means trusting that God really does know what’s best for us—yes, even better than we do! That’s what we call faith. And our faithfulness is supposed to point to God faithfulness.

Which is why when we allow ourselves to be defiled by the wickedness that comes from within, or to be stained by the sinful ways of the world, we obscure the nearness of God. When our religion is less than pure, it gives a counter witness. When those who claim to belong to God fail to care for the most vulnerable—widows and orphans, in the words of St. James—or, even worse, to abuse their power, or prey on the weak, or turn a blind eye, or walk away, or complain loudly but neglect to act, then what the Lord intended to be a sure and inviting pathway to his presence instead becomes an obstacle, a stumbling block. The Greek word for such a “stumbling block” is skandalon—a scandal.

Which, of course, brings us from the experience of ancient Israel to that of the Catholic Church today.

Whether in pinochle or in life, we don’t get to choose our own cards. You have to play the hand you’re dealt. Which is why I think we need to see the darkness and crisis of our times as a call from God: a call to take his law to heart; a call to remember and learn from our past; a call to be faithful—more faithful than ever!—because Jesus Christ will always remain faithful to us.

We who belong to the Catholic Church have a closeness, an access to God that far surpasses even that of ancient Israel. God lives among us, is amazingly near to us, not confined within the walls of a single temple in Jerusalem, but in the Most Holy Eucharist. In the Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood, God is with us in all the tabernacles of the world; in the Bread of Life, the Lord is as close as close can be: dwelling right within us.

In the course of her 2,000-year history, the Church has recorded several Eucharistic miracles. On a few occasions—generally, when faith has grown weak—Catholics have witnessed the Scared Host at Mass visibly, physically turn into human flesh. And when scientific tests on that flesh have been performed centuries later, they always find the same thing: that it’s cardiac muscle. At Mass, Jesus gives us his battered, bleeding heart to unite it with our bruised and wounded hearts. Jesus is the divine law, God’s Word, written in human flesh and blood—flesh and blood he has given to be our food and drink. That’s such an amazing, precious gift! We must never take it for granted! And we must never let our sinfulness become an obstacle—a scandal—that blocks our way or anyone else’s to drawing so very close to Christ when he comes to meet us upon the altar.

I have a wish, a hope, a desire for the Church—and when I say “the Church,” I don’t mean “those guys” who need to make some big changes “over there,” but us folks—each and every one of us—in need of renewal and conversion right here. My hope is that the Church will do far better when it comes to finding her way through these painful, confusing times than I did when it came to learning the rules of pinochle. And that’s because what’s a stake isn’t winning a card game; what’s at stake is dwelling with the Lord, now and forever.

God’s law has been given to guard our integrity. Let us be sure we’ve taken it to heart.

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Will You Leave, Too?

Twenty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time B

Have you ever set down the newspaper or turned off the evening news in the last few months and wondered, “What has happened to this country? How did we end up like this?”

In 1831, French aristocrat and diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville made a nine-month tour of the United States, and wrote a landmark book about the experience—Democracy in America (1835/1840)—upon his return home to France. De Tocqueville spoke highly of much that he’d seen in this still young nation, but also issued a strong, startling warning: that American democracy is dangerous. Carefully considering our form of government, he saw within it strong tendencies toward individualism and consumerism. He observed that it could cause our citizens to embrace thoughtless conformity, as well as to show disregard for both our past and our future. Ultimately, he warns of a tyranny far worse than the one thrown off in 1776: either the despotism of the “nanny state,” which seeks to micromanage our personal lives in every detail, or mob rule.

Sounds just a little too familiar, doesn’t it?

But you see, de Tocqueville wasn’t really worried that this would ever actually come to pass. Can you guess why? Because—he observed—Americans are such religious people. As long as they remain a people of faith—men and women of virtue, with their moral compass firmly set—he believed the United States would resist falling prey to these dangerous temptations. This was not an idea original to him. In 1798, Founding Father John Adams, while serving as our second President, wrote in a letter, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Take note of all our empty churches these days, and you begin to understand something of how we ended up like this.

We see a parallel circumstance in our first reading this Sunday. We hear some of the last words of Joshua, who had been Moses’ right-hand-man during the long journey through the desert and took over the leadership of Israel after Moses’ death, guiding the twelve tribes across the Jordan River and—at long last—into the Promised Land. Joshua was a holy man and righteous, but even under his capable leadership this young nation lost its way. Once they got settled, they also got complacent: complacent in their observance of the covenant and its commands—their God-given “constitution,” if you will. They began to make compromises with the surrounding nations, and compromises with the nations’ false gods. Through their own fault, the land began to lose more and more of its promise. But they were comfortable with this current state of affairs: it was still better than the dessert, you know, and good enough for now.

It’s against this background that we hear Joshua addressing the people, and pointing to their current moment of decision: will they serve the Lord, or serve these foreign gods? It’s bitterly ironic to hear the people answer, “Far be it from us to serve other gods!” They’ve forgotten who they are. They’ve forgotten whose they are. They fail to recognize how they’ve ended up like this.

We see much the same parallel again in the scandals rocking the Catholic Church today. And I’m afraid the situation is going to get much worse before it starts to get any better. I intentionally say “scandals” in the plural because there are really three scandals all wrapped up together: (1) the despicable, disgusting crimes of the abuse of children by members of the clergy; (2) the failure of many priests and bishops to honor their promise of celibacy, engaging in ongoing sexual immorality—particularly with other men; and (3) the apparently systematic efforts of some in the hierarchy to cover these two things up. It leaves Catholics across the nation and around the world asking, “What has happened to the Church? How did we end up like this?”

I spent my recent vacation visiting many good friends—friends who span the entire spectrum of Catholicism: from those who try to get to Mass everyday, to those who try—with limited success—to get to church at least on Christmas. Every one of them wanted to talk about the scandals. Some were quick to point out the changes they think would set things straight: changes to the Church’s understanding of the priesthood, changes to the rules surrounding celibacy, changes to teachings on sexuality, changes to the structures of Church governance. One friend shared that she was approached by a professional colleague who pointedly asked, “How can you still call yourself a Catholic?” (She struggled to answer.) Another friend asked me, “Is there any way that you could remain a priest but sever all your ties to the Catholic Church?” Her concern was for me: “Why should it fall to you—one of the good guys—to explain and defend all this stuff? There’s so much good you could keep doing if you weren’t connected to all this corruption.” Across the board, the folks I talked to were saddened, they were discouraged, they were angry. I’m right there with them.

I can’t help but hear echoes of Jesus’ words in this Sunday’s gospel: “Are you going to leave, too?” It’s kind of hard to argue with those who do.

Jesus asks this sad question at the end of his long discourse on the Bread of Life, from which we’ve been hearing for weeks now. Many who had previously followed him heard this startling teaching on eating his flesh and drinking his blood, and decided it was just too much to take. Notice how Jesus does not respond to their departure: he doesn’t chase them down saying, “I didn’t really mean it! It was only a metaphor!” nor does he offer, “I’m sure we can make a few adjustments—take a few opinion polls—take into account what everyone’s thinking on the matter…” Jesus does not compromise. And he knows full well that those who can’t handle his doctrine of the Holy Eucharist certainly won’t endure that which will make this incredible gift possible: seeing him hanging dead on a cross, and his battered, wounded body risen from the dead.

As usual, it’s Peter who speaks up first: “Lord, to whom could we go?” It might sound like he’s conceding that he’s run out of options: “Well, Jesus, I guess you’re the best we can do right now….” Look carefully, though, and you’ll see that what Peter is really saying is, “Jesus, you’re our only hope! No, I don’t understand everything, either. I don’t understand how you yourself can be the Bread of Life. I don’t understand all you’ve tried to teach us about your Father and his Kingdom. But here’s what I do know: I know you. I know that I love you. And I know that you love me. And I know that I can trust you. Why would I look anywhere else?”

That, my friends, is where we’ve gotten off track. That’s how we’ve gotten into this horrible mess. Like the U.S. government, which continues to hold elections, vote on laws, and collect taxes, regardless of the ethics of those holding office, so the machinery of the Church has continued to turn: Masses are still being said, baptisms and funerals are celebrated, bills are paid and paperwork is filed…but we end up just going through the motions. Like Israel of old, we’ve made compromises with the world around us: instead of changing it, we’ve let it slowly change us. We might have put in place the best policies and procedures conceivable, but they don’t matter one bit—as has become painfully clear—if our hearts just aren’t in it. Being Catholic isn’t a matter of the things we do; it’s a matter of who we are. We’ve forgotten—from the top down—who we are. We’ve forgotten whose we are. We’ve wandered away from Jesus. That’s how the Church has ended up like this.

St. Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, reminds us of who we really are. He reminds us that the Church is meant to be Christ’s spotless, beautiful Bride—with wart or wrinkle of any kind…which means that the sins of any one of us disfigure all of us. Paul reminds us that the Church is meant to be the mystical Body of Christ—we the members, Christ the head, in intimate, living union…which means that when one part of the body suffers, we all suffer together. What does that say to us about walking away from this broken, compromised Church? That it means filing for divorce, when it’s we ourselves who have been unfaithful. It means amputation, and you know what happens when a limb or organ is cut off from the body: it rather quickly dies.

Fr. Henri Nouwen was a Dutch priest who authored many very popular spiritual books in his lifetime. A few years after his death in 1996, a collection of letters to his godson was published. Here’s what Nouwen wrote to Marc in one of them:

Listen to the church. I know that isn’t a popular bit of advice at a time and in a country where the church is often seen more as an obstacle in the way than as the way to Jesus. Nevertheless, I’m deeply convinced that the greatest spiritual danger for our times is the separation of Jesus from the church. The church is the body of the Lord. Without Jesus there can be no church; and without the church we cannot stay united with Jesus. I’ve yet to meet anyone who has come closer to Jesus by forsaking the church.

from Letters to Marc about Jesus (2009)

The Church to which we belong is so much more than our American democracy. It is not a merely social institution, created by common agreement of its members and changed at will. No—the Church is of divineconstitution, our only sure connection to Jesus Christ by God’s own design. Which means that the Church’s constitution is good—very good. The question is: Are we good? For the Church to be who she’s meant to be, we need to truly be good!

The crisis facing the Church right now isn’t “out there” somewhere, for the powers-that-be in Ogdensburg and Rome to take care of. Weare the Church—all of us gathered here today. Which means that these problems are our problems. If the Church is going to be reformed, it’s only because we have been reformed—each and every one of us. When Joshua realized that Israel was losing its way, he didn’t try to tweak the rules governing the entire people; instead, he made concrete changes much closer to home: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”

So, what can we do? What difference can a lone Catholic in Malone make? To begin with, we must recognize that we absolutely must do something. There can be no more status quo, no more simply going through the motions. As I look to the future, I really see only two options before us: either to get serious, or to get out. What does “getting serious” look like? (1) For starters, it means we need to learn our faith. The Catholic faith isn’t based on popular opinion, but on revealed truth. So dust off your Bible. Study the Catechism. People are asking serious questions of us, and they deserve to get clear answers from us—and not just what any one of us happens to think on the matter. (2) We also need to fall in love with our faith—which is to fall in love with Jesus. We need to speak to him daily—in fact, throughout the day—in prayer. We need to regularly receive the sacraments—especially attending Mass on all Sundays and Holy Days, and getting to confession on a regular basis. These sacraments are instruments of grace—and without grace we can’t become whom we’re called to be, we can’t become holy, we can’t become saints. (3) Finally, we need to live our faith—both in public and in private. That means knowing the moral law and obeying it. That means going beyond casual acquaintance with the folks in the next pew and forming intentional community. And that means reaching out to the weak, the questioning, and the suffering—in this time, above all to those souls unspeakably harmed by the evils wrought by the Church and her ministers.

It’s time for all of us to take personal responsibility for our Catholic faith and for the Catholic Church. It’s time for us to hold one another accountable.

Does our Church need a complete overhaul? No. Besides—who are we to attempt to fix what God himself has established? But what the Church does need is for us to remember who we are. What the Church needs is for us to get back to our roots, to get back to basics. What the Church needs is for us to get back to Jesus—to get close to Jesus, to stay close to Jesus.

After all, to whom else could we go? You alone, Lord, have the words of everlasting life. We are convinced, like St. Peter, and have come to believe that you are the Christ, the Holy One, the Only Begotten Son of God. And Jesus—we and convinced and believe that you are here with us in these dark days: here in the Sacrament of your Body and Blood; here—however hard it may be to see right now—in your deeply wounded and shaken Church.

Sunday, August 12, 2018

Explanation, Please

This homily was posted even later than usual. And you didn't see one the last two weeks: the first, because we had a visiting preacher speaking on behalf of the missions, and the second, because I never found the time to type it up. That's the thing: getting these online requires me to carve out 2 hours or so after the Masses...and I'm finding that more and more difficult to do. Which is to say, you'll be seeing these less frequently from me. When time allows, I'll put one up, but it won't be every Sunday. Some have recommended recording my homilies, which I will consider. Thanks for reading all these years, and for your kind feedback. Stay tuned for whatever comes next...

Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time B

Last night, after dinner, I took Fr. Tojo down to the Franklin County Fair. Our main goal was to get some fried bread dough for dessert. But while we were there, I thought I should also give him his first taste of something uniquely American: the demolition derby. On our way to the grandstand, I thought I ought to try to explain what he was about to behold…but how do you explain the demolition derby? As I heard the words coming out of my mouth, it all sounded perfectly ridiculous. (Deacon Nick told me this morning that I should have said, “From what I’ve heard, it’s just like driving in India.”)

How do you explain the demolition derby?

How do you explain the Catholic priesthood?

Today is the eighteenth anniversary of my ordination as a priest. And the readings we have just heard are the very same ones that were proclaimed at my first Mass. At the time, my attention was understandably focused on the gospel, as we hear again from Jesus’ discourse on the Bread of Life—certainly appropriate words when beginning a life of ministry centered on the Eucharist.

But these eighteen years later, I’m thinking I really should have paid more attention to the first reading.

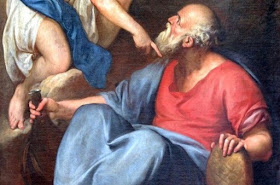

From the First Book of Kings, we hear part of the story of Elijah—the greatest of the Old Testament prophets. We find him hiding under a broom tree, praying for death. Some context tells us why. Elijah was at work during some very dark times. God’s one chosen people had split into two different kingdoms—neither one of them faithful to the Lord’s covenant. They had made foreign alliances, rather than trusting in God’s protection. They had crowned kings for themselves, instead of following God’s divine guidance. And they were worshiping idols and many strange gods—forgetful of the one true God who had claimed them as his own.

To gain God’s people back, Elijah had just won a spectacular and decisive victory over 400 heathen prophets at once—even calling down fire from heaven. But rather than seeing great crowds turning back to the Lord, Elijah sees them turn and walk away. And not only that, but the queen—Jezebel—who was rather fond of these false prophets and their false gods, has now vowed to kill him.

It’s little wonder we hear Elijah praying, “Enough!” Later in the chapter, we hear God ask, “Why are you here, Elijah?” And the prophet lays out exactly how he feels: “I have been most zealous for you, Lord God of hosts, since the sons of Israel have forsaken your covenant, torn down your altars, and slain your prophets with the sword, and I—I alone—am left, and now they seek to take my life.”

I have to admit: sometimes I feel that way, too.

Sure, every newly ordained priest is a bit naïve about just what he’s gotten himself into. But I look back over these eighteen years and have to ask, “Who woulda thunk?” When I was in the seminary, we hade about 125 active diocesan priests in the Diocese of Ogdensburg; today, we have about 50—and only 4 of those are younger than I am. Who woulda thunk? Given my training, I expected—and with good reason—that I would soon enough end up teaching at Wadhams Hall. But a year-and-a-half into my priesthood, the seminary closed. Who woulda thunk?

Who woulda thunk that at the tender age of 35 I’d be appointed the pastor of what was at the time the largest conglomeration of parishes in the diocese? And who woulda thunk that in eight years here, I would have presided over the merger of those four parishes and the closure of two of our churches, and would now be preparing for by far the largest sale in diocesan history of a former church building?

Would woulda thunk that these years would be marked by so much scandal caused by Catholic clergy? Not once, but twice, have I had to announce to parishes that their pastor has been removed from priestly ministry for sexually abusing minors. I’ve heard heart-wrenching tales directly from victims and their families—yes, even here in our own parish. And now such scandal is erupting again. You probably haven’t heard much about it yet, but you will (unless, of course, it gets swept under the rug again). A retired archbishop—a cardinal!—has been brought down in disgrace. In the last month or two, new stories of cover-ups and patterns of sexual sin among priests and bishops have arisen in a number of dioceses, a number of seminaries, in this country and around the world. It’s painful. It’s ugly. It’s discouraging. Who woulda thunk?

St. Paul tells us this Sunday to do nothing that would grieve the Holy Spirit with whom we have been signed and sealed as God’s own. Priests have been sealed twice, and bishop’s three times. How aggrieved must the Holy Spirit be at their heinously sinful behavior?

It kinda makes a guy want to go out and look for a broom tree.

So what’s a priest supposed to do? He’s supposed to do what priests have always been supposed to do. He needs to be holy. That’s the only appropriate response to sin and corruption. And he needs to be faithful—all the more so when infidelity is all around. To be holy, to be faithful: that’s a vocation that is common to us all—the call to be saints—whether you’re in the pew or at the altar. Our vocations depend on one another. I cannot help you become holy and faithful if I am not those things first myself.

Holiness and fidelity take effort and discipline, to be sure. But they also require more than our mere human strength. We look again to Elijah. What is he given when the task seems too difficult and the road ahead too long? God sends him encouragement, in the form of an angel who tells him, “Get up! Keep going!” And God also sends him food and drink, which are clearly no ordinary bread and water since they’re the fuel that allows him to walk 40 days and 40 nights to the Lord’s mountain. We should note that the angel must insistently force Elijah to eat. It would have been much easier for him to quit. But God isn’t giving him an easy way out. He sends Elijah back to his mission with the promise, “I am with you. And those who have remained faithful—however small their number—they’re with you, too. I need you, they need you, to keep going.”

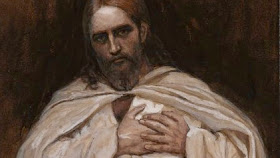

The Lord is still sending messages of encouragement under many disguises. And he’s still feeding us, too—as he will again in a few moments here—with something way beyond ordinary bread: with his own person, with his own flesh, with very the Bread of Life. The Holy Eucharist is the heart of Jesus Christ, God’s eternal love made mortal man, in a form that we can taste and see. You see, with the Eucharist—as with all of priestly life and ministry—it all, always, comes down to love: Christ’s unconditional love for me, my less-than-perfect love for him, my real and true love for you. That’s what keeps me going, despite it all. And it not only keeps me going; it keeps me joyful. The bottom of my chalice and paten are inscribed with words from Psalm 116: “How can I make a return to the Lord for all the good he has done for me?” Yes, there’s much struggle, but there are far more graces and blessings. “I shall take the cup of salvation and call on the name of the Lord.” I continue to do so with joy.

So much has changed in the eighteen years since my ordination, but I am just as certain today as I was back then: that Jesus Christ himself called me to be his priest, and that I’m right where I’m supposed to be, trying my best to do what the Lord wants me to do. That I still love being a Catholic priest even in the midst of so many challenges…makes even less sense than the demolition derby!

How do you explain the demolition derby?

How do you explain the priesthood?

Another way to ask the question: How do you explain love?

St. John Vianney is the patron saint of parish priests. He, too, served Christ and his Church during some rather dark and difficult times. In fact, on more than one occasion, he fled by night from his small parish in the French countryside, hoping to have taken refuge in a quiet monastery before his flock noticed that he was gone. His scheme never worked. Here’s how Fr. Vianney explained the priesthood:

“Only in heaven will [a priest] fully realize what he is.”

“Were we to fully realize what a priest is on earth, we would die: not of fright, but of love.”

“The priesthood is the love of the heart of Jesus.”

My friends, I ask you to please pray for me and for all of my brother priests. Pray, too, for our seminarians and all who are discerning a vocation to the priesthood. Pray that we will be faithful. Pray that we will be holy.

Sunday, July 22, 2018

A Brave Shepherd

Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time B

What were you doing 50 years ago? In 1968, the Vietnam War was raging—as was opposition to it. The Beetles released their “white album,” and Led Zeppelin made its U.S. debut. Other debuts included 60 Minutes, the Special Olympics, and Boeing’s 747 jumbo jet. Yale admitted its first female students. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, as was Robert F. Kennedy. Richard Nixon won the White House. Apollo 8 was the first manned spacecraft to orbit the moon. The Green Bay Packers won the Super Bowl, and the Detroit Tigers won the World Series.

And in the middle of it all, on July 25, 1968—50 years ago this week—Pope Paul VI released his encyclical letter Humanae Vitae (On Human Life), outlining the Church’s position on artificial birth control. It would prove to be one of the most controversial documents in the modern history of the Catholic Church. And that’s strange, really, since it only reaffirmed what the Church had always taught: that there is an intimate, intrinsic bond between sex and marriage because they share the very same purposes: the lifelong, faithful union of husband and wife, and the procreation and education of children. By God’s design, these purposes are not to be separated. This teaching was unanimous among all Christians—despite their many other divisions—until the early 20thcentury.

With the western world in the throes of the sexual revolution, many folks were expecting some change to be announced by Paul VI. But since this teaching was firmly grounded in the Church’s constant doctrine from earliest times, the words of Scripture, and in the very way God put human beings together, the Pope didn’t so much say that he wouldn’t be changing anything, but that he couldn’t.

As the Pope confirmed the Church’s longstanding tradition, countless souls abandoned it. Today, contraception has become the norm—as common among Catholic couples as in the general population, and all-too-often with the quiet encouragement of priests and even some bishops: “We all know what the Church says, but it’s really between you and God. Do whatever seems right for you.” (Those words sound eerily similar to ones spoken by a wily serpent to a couple of newlyweds a long, long time ago.)

Pope Paul VI made some predictions in his 1968 letter—predictions of what would happen if the Church’s teaching went unheeded. He predicted an increase in marital infidelity. He predicted a general lowering of moral standards. He predicted a loss of respect for women. And he predicted government interference in citizens’ reproductive lives.

Every one of his predictions has come true.

Consider these very telling facts… Over the last 50 years the divorce rate has more than doubled; it has actually started to decrease recent, but that’s likely because so few people are now getting married in the first place. The U.S. birthrate has dropped to an all-time low; our population has grown, but only due to immigration, since we haven’t been at a replacement birthrate since 1971. Pornography has become an $100 billion industry, annually producing 20 times more movies than Hollywood; what once—quite literally—lurked about in the shadows is now today influencing everything from childhood development to presidential politics.

In an age that’s so in love with things being “all natural” and “organic,” we seem to make an exception for human reproduction, using whatever artificial means we can devise to either force God’s hand in having a baby or in avoiding one—even if that means eliminating one. This is the only field of medicine I can think of that aims to get a perfectly healthy part of the human body to stop functioning as it should. It’s so ironic that we call them “reproductive rights” when what we actually mean are the many ways we can avoid reproducing. We only want kids on our own terms. We used to see kids as such a priceless blessing; now we feel the need to calculate what they would cost us.

Of course, there’s also the significant, direct impact on the Catholic Church. In our own parish back in 1968, we had 126 weddings and 230 baptisms. This past year—50 years later—we had only 5 weddings and just 14 baptisms. It used to be that you’d see a big family and say (with a smile and a bit of pride), “They must be Catholic!” When was the last time you saw a big family—whether here in church, or anywhere? Nowadays, folks mock or look down upon parents who have many children: “Don’t they know we’ve figured out what causes that?”

Pope Paul VI taught that sex and marriage go together, because loving union and procreation go together. But over these past 50 years, we’ve watched them grow farther and farther apart, such that sex has become increasingly casual (even recreational) and deliberately sterile. It’s no wonder that every Pope since then has echoed the same concerns. Does Humanae Vitae call Catholics to act irresponsibly, and simply have as many kids as they can—even more than they can handle? Of course not. But it does call us to accept and remain open to one of the noblest responsibilities entrusted to us by God: to cooperate with him in the creation of human life.

History has shown that any human society—including the Church—that hopes to survive (leave alone to thrive), does so not because they have lots of wealth, nor because they have military might, nor because they have a highly refined culture, but simply because they have children.

So if the Pope was spot on with all of his grim predictions 50 years ago, might he also have been right about how they could be avoided and corrected?

Our readings this Sunday talk a lot about shepherds—both good and bad. Jeremiah warns against shepherds who mislead and scatter the Lord’s flock. Jesus himself sees the vast, restless crowd gathering around him and, we’re told, “his heart was moved with pity for them”; the original Greek is a good bit stronger: he was stirred in his bowels—felt punched in the gut—to see them so lost, gone so far astray, “like sheep without as shepherd.”

Sheep require vigilant shepherds. They are essentially without defense and cannot manage well on their own. Even when they’re being guided to green pastures and restful waters, they are prone to wandering off and putting themselves in danger.

So it is with sheep. So it is with us—God’s sons and daughters.

Pope Francis has said of his predecessor 50 years later—a man whom he will canonize this October, “He looked to the peoples of the world and foresaw the destruction of the family because of the lack of children. Paul VI was courageous. He was a good pastor, a good shepherd. He warned his sheep about the wolves that were approaching.”

It really all comes down to trust—to our need for an increase of faith. When God creates the first man and woman, the Lord blesses them and gives them this first commandment: “Be fertile—be fruitful—and multiply…” (Gen 1:28). Can we wholeheartedly believe that if we obey this command God will in fact provide all that we need? Do we trust God enough to let him truly shepherd us, believing that when we do, we shall not want? Can we let go of the fear that the Lord won’t come through for us, which sends us off trying to go it on our own? Do we have faith that God is still teaching, still guiding, still protecting his Church through the shepherds he has appointed for us?

If we—sheep and shepherds alike—can grow in this trust, can live with this kind of real faith, then where might we be in another 50 years?