Twenty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time B

Have you ever set down the newspaper or turned off the evening news in the last few months and wondered, “What has happened to this country? How did we end up like this?”

In 1831, French aristocrat and diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville made a nine-month tour of the United States, and wrote a landmark book about the experience—Democracy in America (1835/1840)—upon his return home to France. De Tocqueville spoke highly of much that he’d seen in this still young nation, but also issued a strong, startling warning: that American democracy is dangerous. Carefully considering our form of government, he saw within it strong tendencies toward individualism and consumerism. He observed that it could cause our citizens to embrace thoughtless conformity, as well as to show disregard for both our past and our future. Ultimately, he warns of a tyranny far worse than the one thrown off in 1776: either the despotism of the “nanny state,” which seeks to micromanage our personal lives in every detail, or mob rule.

Sounds just a little too familiar, doesn’t it?

But you see, de Tocqueville wasn’t really worried that this would ever actually come to pass. Can you guess why? Because—he observed—Americans are such religious people. As long as they remain a people of faith—men and women of virtue, with their moral compass firmly set—he believed the United States would resist falling prey to these dangerous temptations. This was not an idea original to him. In 1798, Founding Father John Adams, while serving as our second President, wrote in a letter, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Take note of all our empty churches these days, and you begin to understand something of how we ended up like this.

We see a parallel circumstance in our first reading this Sunday. We hear some of the last words of Joshua, who had been Moses’ right-hand-man during the long journey through the desert and took over the leadership of Israel after Moses’ death, guiding the twelve tribes across the Jordan River and—at long last—into the Promised Land. Joshua was a holy man and righteous, but even under his capable leadership this young nation lost its way. Once they got settled, they also got complacent: complacent in their observance of the covenant and its commands—their God-given “constitution,” if you will. They began to make compromises with the surrounding nations, and compromises with the nations’ false gods. Through their own fault, the land began to lose more and more of its promise. But they were comfortable with this current state of affairs: it was still better than the dessert, you know, and good enough for now.

It’s against this background that we hear Joshua addressing the people, and pointing to their current moment of decision: will they serve the Lord, or serve these foreign gods? It’s bitterly ironic to hear the people answer, “Far be it from us to serve other gods!” They’ve forgotten who they are. They’ve forgotten whose they are. They fail to recognize how they’ve ended up like this.

We see much the same parallel again in the scandals rocking the Catholic Church today. And I’m afraid the situation is going to get much worse before it starts to get any better. I intentionally say “scandals” in the plural because there are really three scandals all wrapped up together: (1) the despicable, disgusting crimes of the abuse of children by members of the clergy; (2) the failure of many priests and bishops to honor their promise of celibacy, engaging in ongoing sexual immorality—particularly with other men; and (3) the apparently systematic efforts of some in the hierarchy to cover these two things up. It leaves Catholics across the nation and around the world asking, “What has happened to the Church? How did we end up like this?”

I spent my recent vacation visiting many good friends—friends who span the entire spectrum of Catholicism: from those who try to get to Mass everyday, to those who try—with limited success—to get to church at least on Christmas. Every one of them wanted to talk about the scandals. Some were quick to point out the changes they think would set things straight: changes to the Church’s understanding of the priesthood, changes to the rules surrounding celibacy, changes to teachings on sexuality, changes to the structures of Church governance. One friend shared that she was approached by a professional colleague who pointedly asked, “How can you still call yourself a Catholic?” (She struggled to answer.) Another friend asked me, “Is there any way that you could remain a priest but sever all your ties to the Catholic Church?” Her concern was for me: “Why should it fall to you—one of the good guys—to explain and defend all this stuff? There’s so much good you could keep doing if you weren’t connected to all this corruption.” Across the board, the folks I talked to were saddened, they were discouraged, they were angry. I’m right there with them.

I can’t help but hear echoes of Jesus’ words in this Sunday’s gospel: “Are you going to leave, too?” It’s kind of hard to argue with those who do.

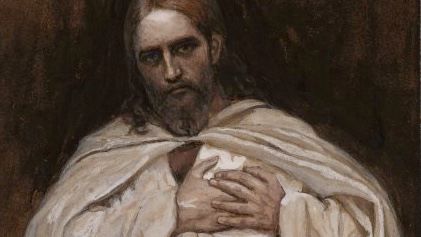

Jesus asks this sad question at the end of his long discourse on the Bread of Life, from which we’ve been hearing for weeks now. Many who had previously followed him heard this startling teaching on eating his flesh and drinking his blood, and decided it was just too much to take. Notice how Jesus does not respond to their departure: he doesn’t chase them down saying, “I didn’t really mean it! It was only a metaphor!” nor does he offer, “I’m sure we can make a few adjustments—take a few opinion polls—take into account what everyone’s thinking on the matter…” Jesus does not compromise. And he knows full well that those who can’t handle his doctrine of the Holy Eucharist certainly won’t endure that which will make this incredible gift possible: seeing him hanging dead on a cross, and his battered, wounded body risen from the dead.

As usual, it’s Peter who speaks up first: “Lord, to whom could we go?” It might sound like he’s conceding that he’s run out of options: “Well, Jesus, I guess you’re the best we can do right now….” Look carefully, though, and you’ll see that what Peter is really saying is, “Jesus, you’re our only hope! No, I don’t understand everything, either. I don’t understand how you yourself can be the Bread of Life. I don’t understand all you’ve tried to teach us about your Father and his Kingdom. But here’s what I do know: I know you. I know that I love you. And I know that you love me. And I know that I can trust you. Why would I look anywhere else?”

That, my friends, is where we’ve gotten off track. That’s how we’ve gotten into this horrible mess. Like the U.S. government, which continues to hold elections, vote on laws, and collect taxes, regardless of the ethics of those holding office, so the machinery of the Church has continued to turn: Masses are still being said, baptisms and funerals are celebrated, bills are paid and paperwork is filed…but we end up just going through the motions. Like Israel of old, we’ve made compromises with the world around us: instead of changing it, we’ve let it slowly change us. We might have put in place the best policies and procedures conceivable, but they don’t matter one bit—as has become painfully clear—if our hearts just aren’t in it. Being Catholic isn’t a matter of the things we do; it’s a matter of who we are. We’ve forgotten—from the top down—who we are. We’ve forgotten whose we are. We’ve wandered away from Jesus. That’s how the Church has ended up like this.

St. Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, reminds us of who we really are. He reminds us that the Church is meant to be Christ’s spotless, beautiful Bride—with wart or wrinkle of any kind…which means that the sins of any one of us disfigure all of us. Paul reminds us that the Church is meant to be the mystical Body of Christ—we the members, Christ the head, in intimate, living union…which means that when one part of the body suffers, we all suffer together. What does that say to us about walking away from this broken, compromised Church? That it means filing for divorce, when it’s we ourselves who have been unfaithful. It means amputation, and you know what happens when a limb or organ is cut off from the body: it rather quickly dies.

Fr. Henri Nouwen was a Dutch priest who authored many very popular spiritual books in his lifetime. A few years after his death in 1996, a collection of letters to his godson was published. Here’s what Nouwen wrote to Marc in one of them:

Listen to the church. I know that isn’t a popular bit of advice at a time and in a country where the church is often seen more as an obstacle in the way than as the way to Jesus. Nevertheless, I’m deeply convinced that the greatest spiritual danger for our times is the separation of Jesus from the church. The church is the body of the Lord. Without Jesus there can be no church; and without the church we cannot stay united with Jesus. I’ve yet to meet anyone who has come closer to Jesus by forsaking the church.

from Letters to Marc about Jesus (2009)

The Church to which we belong is so much more than our American democracy. It is not a merely social institution, created by common agreement of its members and changed at will. No—the Church is of divineconstitution, our only sure connection to Jesus Christ by God’s own design. Which means that the Church’s constitution is good—very good. The question is: Are we good? For the Church to be who she’s meant to be, we need to truly be good!

The crisis facing the Church right now isn’t “out there” somewhere, for the powers-that-be in Ogdensburg and Rome to take care of. Weare the Church—all of us gathered here today. Which means that these problems are our problems. If the Church is going to be reformed, it’s only because we have been reformed—each and every one of us. When Joshua realized that Israel was losing its way, he didn’t try to tweak the rules governing the entire people; instead, he made concrete changes much closer to home: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”

So, what can we do? What difference can a lone Catholic in Malone make? To begin with, we must recognize that we absolutely must do something. There can be no more status quo, no more simply going through the motions. As I look to the future, I really see only two options before us: either to get serious, or to get out. What does “getting serious” look like? (1) For starters, it means we need to learn our faith. The Catholic faith isn’t based on popular opinion, but on revealed truth. So dust off your Bible. Study the Catechism. People are asking serious questions of us, and they deserve to get clear answers from us—and not just what any one of us happens to think on the matter. (2) We also need to fall in love with our faith—which is to fall in love with Jesus. We need to speak to him daily—in fact, throughout the day—in prayer. We need to regularly receive the sacraments—especially attending Mass on all Sundays and Holy Days, and getting to confession on a regular basis. These sacraments are instruments of grace—and without grace we can’t become whom we’re called to be, we can’t become holy, we can’t become saints. (3) Finally, we need to live our faith—both in public and in private. That means knowing the moral law and obeying it. That means going beyond casual acquaintance with the folks in the next pew and forming intentional community. And that means reaching out to the weak, the questioning, and the suffering—in this time, above all to those souls unspeakably harmed by the evils wrought by the Church and her ministers.

It’s time for all of us to take personal responsibility for our Catholic faith and for the Catholic Church. It’s time for us to hold one another accountable.

Does our Church need a complete overhaul? No. Besides—who are we to attempt to fix what God himself has established? But what the Church does need is for us to remember who we are. What the Church needs is for us to get back to our roots, to get back to basics. What the Church needs is for us to get back to Jesus—to get close to Jesus, to stay close to Jesus.

After all, to whom else could we go? You alone, Lord, have the words of everlasting life. We are convinced, like St. Peter, and have come to believe that you are the Christ, the Holy One, the Only Begotten Son of God. And Jesus—we and convinced and believe that you are here with us in these dark days: here in the Sacrament of your Body and Blood; here—however hard it may be to see right now—in your deeply wounded and shaken Church.